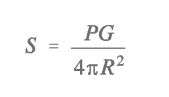

In the “base equation” below, the antenna’s power gain factor (G) is displayed in the numerator on the right side of the equation.

What is Antenna Power Gain?

Power gain of an antenna is the ratio of the power radiated by an antenna in a specific direction compared to the power radiated by an isotropic antenna (which radiates equally in all directions) with the same input power.1

The conversion from decibels (dB) to numeric gain is necessary because:

- Decibels are a logarithmic unit, while actual power ratios are linear.

- The formula G = 10^(dB/10) converts the logarithmic scale back to a linear scale.

- This conversion allows for direct numerical calculations and comparisons of antenna performance.

Would you like me to elaborate on any part of this explanation?

the difference between logarithmic and linear units in the context of decibels and power ratios.

Linear units: Power ratios are linear. This means that if you double the power, the ratio doubles. For example:

- A power ratio of 2 means twice as much power

- A power ratio of 4 means four times as much power

- A power ratio of 100 means one hundred times as much power

This linear relationship can lead to very large numbers when dealing with significant power differences, which can be cumbersome to work with.

Logarithmic units (decibels): Decibels (dB) use a logarithmic scale. In a logarithmic scale, equal intervals represent equal ratios rather than equal differences. This compression of the scale is particularly useful for representing a wide range of values.

For decibels:

- 3 dB represents approximately double the power

- 10 dB represents 10 times the power

- 20 dB represents 100 times the power

- 30 dB represents 1000 times the power

This logarithmic nature of decibels allows us to represent both very small and very large power ratios with more manageable numbers. It’s especially useful in fields like acoustics and electronics where the range of power levels can span several orders of magnitude.

The formula G = 10^(dB/10) is used to convert from this logarithmic scale back to the linear power ratio. This is necessary when we need to perform arithmetic operations or when we want to understand the actual power ratio rather than its logarithmic representation.

Certainly. Let’s look at some examples to illustrate the relationship between decibels (logarithmic) and power ratios (linear).

Example 1: Converting from dB to power ratio

Let’s say an antenna has a gain of 20 dB.

Using the formula: G = 10^(dB/10)

G = 10^(20/10) = 10^2 = 100

This means a 20 dB gain represents a power ratio of 100. The antenna radiates 100 times more power in a specific direction compared to an isotropic antenna.

Example 2: Converting from power ratio to dB

Now, let’s say we have an antenna with a power ratio of 50.

Using the formula: dB = 10 * log10(G)

dB = 10 * log10(50) ≈ 17 dB

Example 3: Comparing linear addition vs. dB addition

Let’s consider two amplifiers in series:

- Amplifier A has a gain of 10 (linear) or 10 dB

- Amplifier B has a gain of 100 (linear) or 20 dB

Linear multiplication: 10 * 100 = 1000

dB addition: 10 dB + 20 dB = 30 dB

Converting 30 dB back to linear: 10^(30/10) = 1000

This shows how adding dB values corresponds to multiplying linear power ratios.

Example 4: Visualizing the compression

Power Ratio | dB

1 | 0

10 | 10

100 | 20

1,000 | 30

10,000 | 40

100,000 | 50

As you can see, while the power ratio increases by a factor of 10 each time, the dB value only increases by 10. This demonstrates how dB compresses large ranges into more manageable numbers.

These examples highlight why it’s often more convenient to work with dB in antenna and signal analysis, but also why we need to convert back to linear values for certain calculations.

- FCC Bulletin Page 11 ↩︎